Walter Sommers lived with gratitude for the life he was given. When asked to look back on his 101 years, he beamed, “I have had a good time in life, it couldn’t have been better.” He lived each day with optimism and purpose, with a strong sense of duty to bear witness to the history he experienced, and to pass this history forward to future generations. When asked about his optimism, he would smile and say: “Life turns out better if you start each day seeing the glass half-full, not half-empty.” For 101 years, Walter chose optimism over pessimism, hope over fear. He lived a long, full life, but to Walter’s family and friends, he didn’t live long enough.

Walter died peacefully in his sleep on February 17th. He is remembered by family and friends as an inspiring presence, modest and unassuming despite all his accomplishments, determined to meet what life gave him, squarely and honestly. Walter’s grandson Devin remembers “my granddad always amazed me with his utter modesty. There’s nothing he didn’t see and yet there was never a touch of aggrandizement in the way he spoke, always warm and loving—and so practical.” And Walter’s granddaughter Alex loved her grandfather’s gift to inspire and uplift everyone around him naturally and with ease: “My grandfather cared for others deeply and never lost focus of the things that mattered to him. I never heard him say anything unloving, which I’ve taken for granted my whole life, but I now understand is remarkable.”

Walter passed on his wisdom through storytelling; he instinctively understood the ancient power of stories to teach life lessons and historical truth. “If you don’t study history and learn its lessons,” Walter often said, “you are condemned to make the same mistakes all over again.” His granddaughter, Rachel, recalls how her grandfather used stories as a bridge to connect with others, extending a story like an outstretched hand in greeting, an invitation to connect across continents and generations. “My grandpa’s stories live in us now, ways we understand our own lives and loves, fears and sorrows. We touched history through his stories, and it is our responsibility—and joy—to pass his stories forward to our children.”

Family and friends, sitting around the kitchen table or drinking a cup of coffee together, would say–tell us the story about the cow in the basement; tell us about your first haircut, about surviving Kristallnacht, landing as an immigrant in America with a quarter in your pocket, fighting at Okinawa, helping to integrate a restaurant—and there was always a story about how to meet life when it rises up, demanding resiliency and responsibility, courage and tenacity. “Things happen in life,” Walter would say in his folksy and wise way, “so it is up to you to respond—and it is your response that counts.” No matter how many times family and friends heard a story, they wanted to hear it again. Walter’s dear friend Steve Fear remembers how he loved watching Walter travel back in his memories to find a story, always stories ready for telling, and finishing each story with a smile, a nod, and the words: “I have had a good life.” And Grandson Demian reflects that “only a fortunate few get the luxury of experiencing 101 years in the world. With all that time gaining knowledge, experience, and wisdom one becomes a living piece of history. Fortunately for my grandfather’s family, he shared his wisdom garnered over such a vast, daunting, and impressive life.”

That story about the cow in the basement was a favorite of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1920, there was a shortage of milk in Germany. The Treaty of Versailles which ended World War I imposed severe reparations on Germany, and most of the dairy cows were confiscated and taken to France. Walter’s father was determined that his newborn son would have milk, so he went to the countryside, purchased a milk cow, and under cover of darkness moved the cow into the basement of his apartment building. What did the apartment tenants think about the cow, listeners would ask? “They weren’t happy in the beginning, “Walter would say with a laugh, “but when they saw that the cow produced milk and cream for the entire building, they decided the cow was a good thing.”

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, on December 29, 1920, to Julius and Helen Sommer, Walter’s family roots in Germany can be traced to the 18th century. One of Walter’s stories featured his grandfather’s service in the Prussian army in the Franco-Prussian war, for which he received a medal from Kaiser Wilhelm for taking care of the Prussian army’s horses. Many of Walter’s stories, like the story about his grandfather, or the cow in the basement, reflect how secure the family felt in Germany before 1933. Walter’s stories recall the birth of his beloved sister Lore, family hikes in the Taunus mountains, summer trips to Switzerland, field hockey games, school days with strict schoolmasters, and working alongside his father in his chain of 38 stores, Wittwe Hassan, where Julius sold fine coffee, wine, and chocolate. About those strict schoolmasters at the Muster Schule, Walter would gesture to show how they pointed their fingers in the air to make their points, while teaching English, Spanish, and French, languages that opened up Walter’s skills to navigate what would be asked of him, securing an apprenticeship with a Hamburg export company, securing a visa for his family to enter the United States and then settling his family in a new country with a new language.

Walter’s stories about his life in Germany were filled with a before and after—before the rise of Hitler and the Nuremberg laws, there was a life of prosperity and peace, family outings and school trips, but after 1935, Walter was expelled from his school and hockey club; his family could no longer own a home; his father was forced to sell his 38 stores; their German Citizenship was revoked. On November 9, 1938, Kristallnacht—the Night of Broken Glass— retail stores, including Wittwe Hassan, were destroyed; synagogues burned; some 30,000 Jewish men arrested and taken to concentration camps. Among these men was Julius Sommer, Walter’s father, who was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. For over six weeks, and through efforts on Walter’s part and through bribes and efforts of Julius’s business associates, Walter secured his father’s release from Buchenwald.

Although Walter spoke English when applying for a visa at the American consulate, he was unable to secure a visa for his family until he located a relative in America willing to sponsor the family. Walter searched for months until he found a cousin of a cousin who agreed to sponsor the Sommer family on the condition that they would ask for nothing but sponsorship. With visas in hand, Walter and his family fled for Holland, leaving behind eleven family members who would be murdered in concentration camps. From Holland, the family boarded the Dutch ocean liner in Rotterdam and landed in New York. On the voyage to America, Walter met a college student who asked Walter what he knew about America, quizzing him on the state capitals. When asked for the capital of Wisconsin, Walter gave the correct answer—Madison—and was rewarded with a quarter to start his American adventure. Arriving in New York at age 18, with a quarter in his pocket, Walter felt as if the Statue of Liberty was welcoming him, personally, to his new home.

Within two days of arrival in New York City, Walter headed to the garment district, where he persuaded the owners of French Fabrics to hire him to wrap fabric remnants. About that moment, Walter would say “we looked like refugees in our European clothes; we were strangers in a new country that didn’t welcome German-Jewish refugees.” And about that first quarter, Walter said “Twenty-five cents in New York City would buy a big piece of apple pie with a tremendous scoop of vanilla ice cream; it would buy five loaves of day-old bread; and five subway rides. That quarter was a lot of money in those days.”

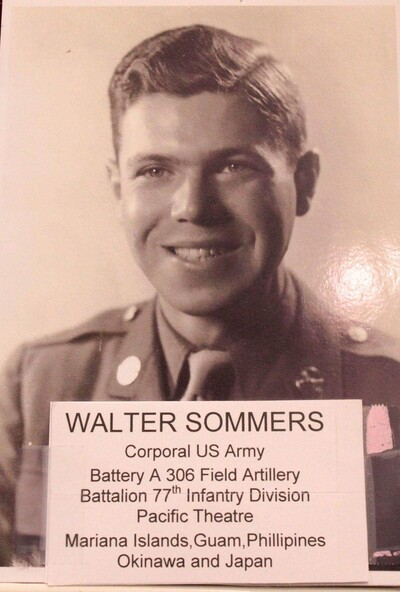

Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, Walter went to the recruiting office to enlist. Although first rejected as an “enemy alien,” and told to go back to Germany, he was later drafted in 1942, volunteering for artillery. As he explained. “Rule number one was do whatever you can to stay alive, and I knew I would be safer in field artillery than infantry.” Assigned to Battery A, 306th Field Artillery Battalion, of the 77th Infantry Division, known as the Statue of Liberty Brigade, Walter served as a forward observer and calculated artillery fire control in the Pacific. He participated in three major island landings —Guam, Leyte, Okinawa—and was one of the first American combat soldiers to set foot on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido.

It was in the army, Walter would say, that he learned to be an American, picking up American slang and customs, and becoming an American citizen in 1943. During his citizenship hearing, the judge remarked that the name Sommer was too German and that he would be known as Sommers, an American name. Photos of Walter at this time show his self-awareness, proud to fight for his new country and grateful to America for harboring his family. Throughout his long life, Walter celebrated his citizenship: “I love America,” he would say, “this country saved my life. We’re not leaving here; here matters.”

After the war, in 1946, Walter started Sommers Plastics Company that produced synthetic leather and soon gave Walter a financial toehold in America, enough of a toehold, as he would say, to buy his sweetheart, Louise Levite, a wedding ring. Louise, his sister Lore’s best friend, and the daughter of his father’s business partner, wrote the best letters to Walter during the war. Walter and Louise were married in 1947 and for 73-years formed a close, loving partnership as brave companions over their decades together. Walter often said that if he could write a script about how to have a happy married life, he would write about his marriage to Louise—and he wouldn’t leave one thing out.

In 1948 Louise’s uncle, Salo Levite, asked Walter to work with him at the Meis Department Store in Terre Haute. Walter eagerly accepted the offer to leave New York City for a safe, small Midwestern town. Walter first saw Terre Haute in the winter of 1943 when his troop train bound for the Arizona desert broke down. Walter described the day: “The temperature was below freezing, with 6 inches of snow on the ground. I was ordered to guard the Howitzers on the flat car. I had only been there a few minutes when a group of local people showed up with hot coffee and donuts; the Red Cross came with coke and cookies. I couldn’t believe how friendly the people were in Terre Haute. It was such a heartwarming experience burned into memory.”

For forty years, Walter had a successful business career at the Meis Stores as Vice-President and Merchandise Manager, a buyer for ladies’ coats, furs, and suits. He helped expand the one Meis Store into 10 stores in Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky. He loved customers—“the customer is always right”—he would tell his children. And his children remember their family dinners, listening to their fathers’ stories about what the customers bought and returned, liked and disliked. Long after he retired, customers would stop him in restaurants and proudly say “You sold me my navy cashmere coat in 1961” or “Remember that tweed coat with a raccoon collar you sold me in 1972.” Walter understood that customers are the most important part of retail, and he loved the easy-going friendships with his loyal, devoted customers who showed up, year after year, for their fall jackets and Easter coats.

In 1988, Walter retired and began a new career as a volunteer. About retirement, Walter liked to say, “it isn’t a place where you go to prepare to die; it is a place where you get involved with new possibilities, see a new future for yourself.” And a new future he claimed. After first volunteering for the Red Cross, Hospice, and Union Hospital, he found a new possibility as an English language instructor at the Terre Haute library. Knowing English had opened a world for him, and he wanted to do the same for his students. One of his students, Myousun Kim, admires how her English lessons with Walter began at the library and continued on field trips to the supermarket, ice cream shops, voting booths, and to museums where there was always new vocabulary to learn. Upon her return to South Korea, Myouson opened an English School in Seoul. “If you hear a Korean speaking English with a German accent,” Walter liked to say, “you probably are meeting one of Myousun’s students.”

In retirement, Walter found a new future, with a quest to understand, intellectually and personally, what had occurred in Germany. How could it have happened to his family, proud Germans who had fought in the Franco-Prussian War and WW I, that their country deprived them of their home, their citizenship? How could a Rabbi, in 1934, urge his family not to leave—to say to his father, “Germany is our country; we’ve seen hard times before; we need to stay.” He had arrived at a point in his life where he had time to pursue his quest by reading thick volumes of European history and returning to Frankfort to retrace his steps, visit his former home, where the cow lived in the basement, and speak at his beloved school, Muster Schule. Always he told stories and asked questions.

In 1993, when Eva Kor invited Walter to become a docent at Candles Holocaust Museum, he took his personal stories and messages about history to thousands of visitors over the next 27-years, speaking and volunteering at the museum and local schools. Describing himself as a student of the Holocaust, always learning and asking questions, he offered museum visitors each Wednesday and Friday afternoon, a chance to ask their own questions about the Holocaust, and to feel as if they could touch history, hearing it from someone who had experienced so much of it. Museum visitors, especially high school students, were mesmerized by his stories. With his dear friend Terry Fear, he created powerful presentations, sometimes lecturing to as many as 150 students, encouraging students to face history, speak openly, and confront religious and ethnic prejudice. Students responded enthusiastically to Walter, treating him like a local celebrity, taking selfies with him and posting them on social media, even making videos about him for their school projects. In 2016, in recognition of Walter’s efforts to promote peace and tolerance through Holocaust education, Walter was awarded the Cross of the Order of Merit, Germany’s highest civilian award. In 2021, Walter was awarded The Honorable Order of Saint Barbara, the highest recognition for service in the Field Artillery for those who have served with selflessness and demonstrated the highest standards of integrity and moral character.

On Walter’s 100th birthday, Leah Simpson organized the Candles Museum community to send Walter 100 cards. Cards arrived from all over the world, around 350 in total, expressing love and gratitude for Walter’s presentations and memorable stories. One card read: “To know you is to know that this is one more day that hate loses. This is one more day we can learn to do what is right in the world. In you, our world knows the best of humanity.”

Often asked how he wanted to be remembered, “That’s easy,” he would say. “When I am gone, I want people to remember me as a family man who was blessed with a wonderful life.” And he would point to one of his favorite photos, his arms wrapped tightly around Louise’s waist, in the fullness of their life, and say “that’s where it all began.” He took great pride in his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, their accomplishments and their joys—everyone who knew Walter knew the names of his treasured grandchildren—Demian, Devin, Rachel, and. Alex—and the names of his adored great-grandchildren—Asher, Isabelle, Lailah, and Oren. He followed his grandchildren through college, graduate school, law school, to Berlin and to Beijing, followed them as they became lawyers, artists, professors, ultra-marathon runners, writers, designers, fathers and mothers themselves. And he took great pride in the way his grandchildren chose their wonderful partners—Liz, Yuval, and Brian—whom he loved as his own grandchildren.

Walter leaves behind his grieving family—son Ron and daughter-in-law Charles Mary Kubricht; daughter Nancy and son-in-law Joshua Alper; grandchildren Demian and Liz Fore; Devin Fore and Yuval Boim; Rachel Chunnha, Alexandra Hays, and Brian Watterson; great-grandchildren Asher and Isabelle Fore, and Lailah and Oren Chunnha; nieces Judy and Linda Gerson, Elizabeth and Barbara Adler, Susan Chapman, and nephew James Adler; brother-in-law Ron Levite; beloved friends Steve Fear, Bill Gilmore, Vicki Cotrell, Angelika Rieber, Jackie Silver, Leah Simpson, Jan Benton, Rick and Angie Kelsheimer; and his devoted caregivers Tamika Shavers, Lynn Patterson, and Elisha Medrano.

Walter Sommers was a son, brother, husband, father, uncle, grandfather, great-grandfather, and friend—he was much beloved. We will always miss the sound of his voice, his love for life.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in Walter’s memory to Candles Holocaust Museum.

A memorial gathering will be held in the spring. In the meantime, we encourage everyone to Google Walter Sommers for the videos and museum presentations that let you hear his story in his wise and folksy voice.

To send a flower arrangement to the family of Walter Martin Sommers, please click here to visit our Sympathy Store.